Presse, Juillet 2016

Photos © André Morin

The illusions at La Cité Radieuse, a project called À Ciel Ouvert, are his latest works.

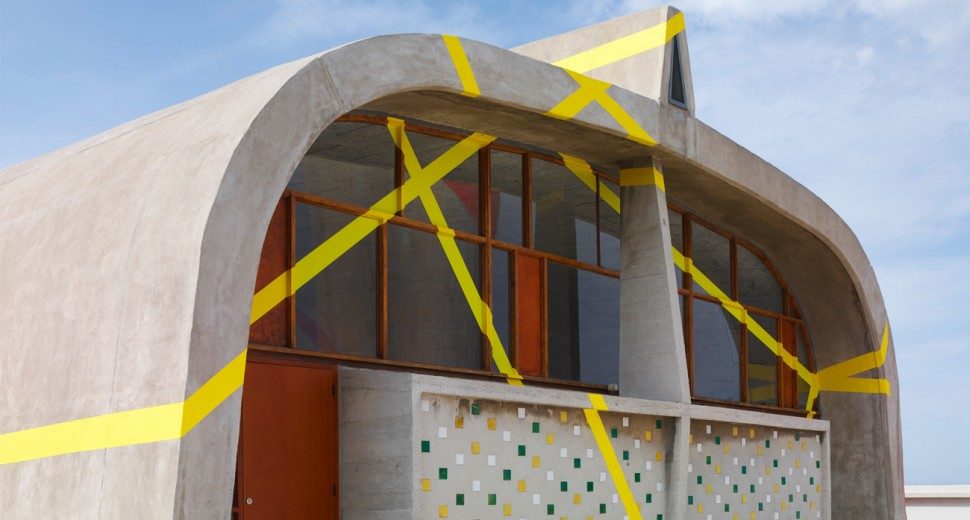

A BUILDING BY Le Corbusier isn’t the kind of thing you deface lightly. The Swiss-French architect was a pioneer of the modernist movement and is renowned for the humanizing touch he brought to crowded cities. Just last week, UNESCO added 17 of his projects to its list of World Heritage Sites. So it may surprise you to learn that one of those projects—a building in Marseilles, France called La Cité Radieuse—was recently covered in what look like random bands of red and yellow paint.

From most angles, the shapes make little sense. But move to the right vantage point and the fragments merge into clear, continuous shapes that seem superimposed on the building. It looks as though someone took a photo of the building, developed it, and screen-printed circles and triangles directly onto the image.

The paint job is the work of Felice Varini. The Swiss-born, Paris-based artist specializes in perspective-dependent projections called anamorphoses. These visual tricks have a long history in photography and painting, but for nearly 40 years, Varini has been designing them for huge, unconventional canvasses; the artist has bedecked train stations, the Grand Palais, and entire city squares in these large-scale optical illusions.

The illusions at La Cité Radieuse, a project called À Ciel Ouvert, are his latest works. When the French designer Ito Morabito (he goes by Ora-Ito) bought the roof of the building in 2010, he decided to do away with the gym, the track, and the solarium that had stood there for years. In their place he built an open-air art center called Marseille Modulor—MAMO, for short. The space is designed according to unrealized blueprints Le Corbusier left behind. It’s architecture on top of famous architecture. Varini’s work has the charming effect of showing visitors a way to experience it all anew.

Varini prefers not to assign too much meaning to the shapes and patterns he chooses for his installations. His designs are not based on history, or art, or even the canvas upon which they live. Varini first visited La Cité Radieuse to begin plans for À Ciel Ouvert. He says Le Corbusier’s building is clearly an awe-inspiring place, but once he began to work, “I forget that it’s Corbusier, and I make a painting,” he says.

Varini says he thinks about the human body, and how he can alter the body’s relationship to its surroundings. With a design in place, Varini then beams the patterns onto surrounding surfaces with a light projector, and starts drawing and painting shapes into place. His installations can take up to two years to paint. À Ciel Ouvert, by comparison, was a rush job, taking Varini just two months to complete.

For permanent murals, Varini will paint directly on a building’s facade. But for À Ciel Ouvert, he relied on large pieces of painted aluminum, which he applied to the building like giant metal stickers. That aluminum will come down in October. Until then, Varini says, “maybe people don’t understand exactly what I’m doing, but they are experiencing something new.” Even for those familiar with La Cité Radieuse, searching for Varini’s colorful shapes will help them see it from a different angle.

Text by Margaret Rhodes