Presse, Avril 2013

Photos © Amy Serafin, James Reeve

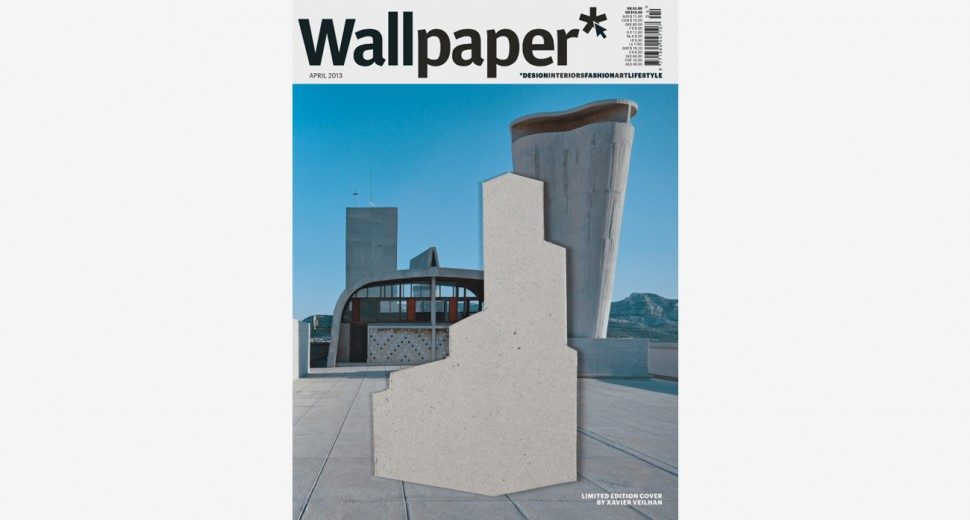

Designer Ora-Ïto is transforming the rooftop gym of Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseille into a contemporary art space. And that’s just the start of the city’s cultural revolution.

Modernist icons like Le Corbusier’s rooftop gymnasium at Cité Radieuse don’t come on the market very often. But three years ago, French designer Ora-Ïto learned that unique space in Marseille was for sale. He didn’t know what to do with it, or exactly how he would pay for it, but he knew he had to have it. It was summer, so he wrote a cheque and hoped the seller would be on vacation long enough for him to find the funds to cover it.

The gamble paid off. One June 8, Ora-Ïto will inaugurate his renovated rooftop as contemporary art space called MAMO. The name is a blend of Marseille and Le Corbusier’s Modulor theory, as well as a sly nod to other art world acronyms.

Ora-Ïto was born in Marseille in 1977, the son of designer Pascal Morabito. His real name is Ito Morabito; he adopted the pseudonym Ora-Ïto when he created his own (very successful) design brand. Though he lives in Paris, he maintains strong ties to Marseille, where he has a weekend home and an old fort on an island. As for the rooftop: « I couldn’t imagine it would ever be for sale », he recalls, « Nobody could. »

Le Corbusier built the Cité Radieuse between 1947 and 1951. He conceived it as a vertical city, with apartments, a restaurants, shops, a nursery school and a gymnasium. Like most sports clubs, the one here was used by a fraction of the people who paid for it; in this case the building co-op. Those residents who didn’t use it grew tired of contributing to its upkeep. So they privatised the gym, and when the new owner retired three years ago, he put it up for sale.

Ora-Ïto realised it was a risky purchase; the Cité Radieuse is a national heritage site, and the roof structure was classified as a sports club, wich meant the new owner would have to maintain it as such. Fortunately, the building co-op voted to let him change the use to an arts centre, freeing him up to restore the structure. The designer chose not to inject his own style into the project, even if he admit it wasn’t always easy to keep his healthy ego in check. « When I drew up the plans in the beginning. I was adding things, it was Ïto in Corbu, and then there was this little voice saying : non non non, clam down, you! » Michel Richard, the director of the fondation Le Corbusier, was impressed by Ora-Ïto’s dedication to historical accuracy: « We were worried that nobody would buy the gym and it would fall into ruin, he says. Ora-Ïto’s project, to give this building an artistic function, is everything we could have wished for ».

While consulting a book on Le Corbusier, Ora-Ïto came across an old photograph of the roof that looked different from the space he had acquired. That’s because in the late 1950s, a 150 sq m extension had been stuck onto the gym’s façade. When the building was classified in 1986, the addition (he calls it ‘the wart’) was included as part of the classification. « in the photo I saw the original façade with its old wood panels and shutters designed by Charlotte Perriand. It was superb. And I thought, I’ve got to demolish that thing right away. »

Once he got permission to tear it down, what remained was a large terrace with a stunning view of the sea and mountains, a concrete solarium, a shower room studded with coloured tiles and a concrete overhang to one side. The newly exposed façade had a grid of concrete separations like a Mondrian painting.

Paid for jointly by Ora-Ïto, the building’s co-owners and the french state (wich took an early interest in the project), the 7m euros renovation has extended to the entire rooftop, not just the part that belong to him. Inside the part that belong to him. Inside the former gym, Ora-Ïto is creating a café, a shop and artist’s residences alongside the vast exhibition space. He’ll furnish one residence with a kitchen from a Cité Radieuse apartment that he picked up at auction. As he explaines: « I’m only buying vintage furniture, no reproductions. »

In winter, the space will primarily serve the locals, inviting architecture schools to visit. It is in the summer that MAMO will take on an international dimension, hosting a major solo exhibition for four months each year. « The whole world is here then », says Ora-Ïto, « in Nice, Cannes, Saint-Tropez, Monaco. Abramovich can hop over in his helicopter, it’s nothing for him ».

The French artist Xavier Veilhan will inaugurate the space in June, making MAMO part of his Architectones series, installations created for exceptional architectural sites around the world. His show is a homage to the Cité Radieuse and its creator. « Le Corbusier had a lot of trouble getting this building done. » says Veilhan. « It’s interesting to go back and look at the stages of a building that has become such an institution, and to try to imagine how uncertain it once was. »

Back when Le Corbusier was a rising star, Ora-Ïto’s great-grandfather, also an architect (in Argentina), lost a competition to Le Corbusier and retired, realising he had fallen out of step with the times. Modernism had arrived. It is somehow fitting that his descendant is now turning one of Le Corbusier’s masterpieces into a contemporay destination.