Presse, Avril 2013

Photos © Olivier Amsellem

French designer Ora-Ïto is converting the famous Marseille roof terrace into a haven for contemporary art.

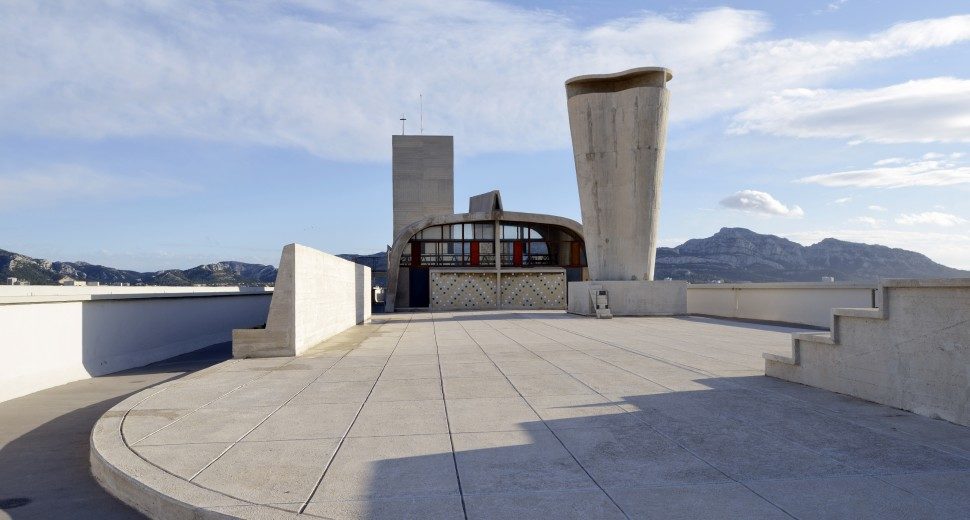

“Welcome to my place,” says Ito Morabito, perched on the balustrade of the most famous rooftop of any 20th-century building. Behind the young French designer, concrete forms gleam in the midday Marseille sun: a great ventilation stack flares out like a sculptural vase; a paddling pool nestles beneath a classroom on stilts; children clamber on a mock-mountain of rugged rocks.

The roof terrace of Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse apartment building, completed in 1953, has long been the symbol of the sun-drenched ideal of Mediterranean modernism – a park in the sky for the residents of this brave new vertical city. It stretches out like the deck of an ocean liner, with rocky mountain peaks to one side, the open sea to the other, a landscape of collective leisure suspended 18 storeys up in the air. And now it has a new owner, with big ambitions.

“This will be the reason people come to Marseille,” says Morabito, who has never been one to shy away from big claims. Now 35, he was catapulted to fame 10 years ago when he designed a series of fake products for luxury brands, complete with fake advertising campaigns, under the pseudonym Ora-Ïto. These fraudulent objects, and the audacity with which he promoted them, created so much hype the very brands he was pirating began to beat a path to his door with real commissions. His design skills have since proved a little less successful than his capacity as a PR stuntman, but that has not hindered his plan to transform this little piece of Corbusian heritage into an international art centre. It is a story as unlikely as his own rise to fame. So how did it come about?

Beneath the roof terrace, the cliff-like stack of apartments of the Cité Radieuse is peppered with shops and offices, a hotel and restaurant, doctor’s surgery and nursery school. In Corb’s vision, the building’s 1,600 residents would shop, eat and learn together – while up on the roof they would exercise as one in a purpose-built gym, paid for by the residents’ association. Only, like a lot of gyms, most people that paid for it didn’t actually use it. As residents grew tired of contributing to its upkeep, the gym was privatised, and when the owner retired three years ago, he put it up for sale.

“As soon as I heard it was on the market, I jumped on a train,” says Morabito, who was born in Marseille, the son of jeweller Pascal Morabito, but now runs his studio from Paris. “I grew up knowing this building, so I couldn’t resist that chance to own such an important piece of it.”

While many others had the same idea, he says his bid was favoured by the building’s co-owners because he was one of the few who proposed restoring the rooftop back to its original state. It had become rundown and poorly maintained, its abandoned spaces a site of illicit trysts. “It was the fucking place,” he grins.

“I had a book of original photographs, and it looked really different,” he says. “I realised there was this great big wart that had been added in the 1950s as an extension to the gym – and it was listed with the rest of the structure when the building became a protected monument in the 1980s.”

Lengthy negotiations, with the help of the Fondation Le Corbusier, have allowed him to slice off the wart. This revealed an expansive sun deck complete with a shower room studded with coloured tiles, and the Fondation supplied original drawings to enable restoration of the structure – including a set of beautiful timber sliding doors, designed by Corb’s collaborator Charlotte Perriand.

At a cost of €7m – jointly funded by Ora-Ïto, the building’s co-owners and the French state – the entire rooftop has been immaculately restored, while work is underway to transform the former gym into an arts space, cafe and artists’ residences, which will host a site-specific installation for four months over the summer each year. The project is christened Mamo – the “Marseille Modulor” – in a riff on Le Corbusier’s system of measurement, and a cheeky inversion of New York’s MoMA, which seems appropriate given how Ora-Ïto made his name.

“I want it to be like a boxing match between Le Corbusier and the artist,” says Morabito, who has lined up French sculptor Xavier Veilhan to be first in the ring with one of his Architectones installations – a series of works developed for specific architectural sites around the world. During the winter months, the space will host lectures and workshops with architecture schools.

Set to open in June as part of Marseille’s 2013 Capital of Culture extravaganza, only time will tell whether the residents of the Cité Radieuse will find a contemporary arts space more useful than a gym, or whether it is another step in the promotion of the Ora-Ïto brand. Either way, it has spurred on an overdue restoration, and it is a valuable addition to the city’s emerging network of arts venues. As Morabito smiles, taking in the view of his new domain: “We will make a big noise when it opens. We are a very big – how do you say – show-off.”